Orthodox Christianity (GCSE Religious Studies)

In GCSE Religious Studies, exploring the diverse landscape of Christianity is essential for accessing the top grades. Beyond Roman Catholicism and the various Protestant denominations, students may consider Orthodox Christianity – a vibrant, ancient, and distinctive branch that represents a significant portion of the global Christian population (roughly 12%). Often referred to as "Eastern Orthodoxy," it offers a unique perspective on faith, worship, and theology, rooted in the Byzantine church, that is crucial for a comprehensive grasp of global Christian faith.

In this blog, expert tutors breakdown the history, beliefs and practices of this fascinating denomination, comparing it to other forms of Christianity on the GCSE RS syllabus. Finally, we explain how you can apply this extended subject knowledge to your exams.

The Great Schism and Apostolic Continuity

Orthodox Christianity traces its origins back to the early Christian communities established by the Apostles (the original disciples of Jesus) within the eastern half of the Roman Empire. To appreciate this unique heritage, we must cast our minds back to the history of ancient Rome.

The Roman Empire was formally divided into two administrative halves by Emperor Diocletian in 286 CE in an attempt to stabilise its vast territory. However, a combination of overstretched borders and the persistent migration of Germanic tribes from the north ultimately led to the Western half's collapse in 476 CE. This triggered a period of political upheaval and fragmentation, sometimes referred to as the Dark Ages. In the resulting power vacuum, the Bishop of Rome, or Pope, was uniquely positioned to assert authority. As the only institution to survive the collapse of the Roman Empire largely intact, the papacy gradually filled this void, solidifying its position as the pre-eminent religious and cultural authority in the West.

By contrast, the Eastern Roman Empire, known as Byzantium, did not suffer collapse to Germanic invaders. It endured and flourished for another thousand years, continually governed by Roman emperors, such as the influential Justinian (527-565), until its final conquest by the Ottoman Empire in 1453. With its capital at Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), Byzantium maintained a strong imperial court and a more flexible model of religious authority. Unlike Western Christianity, which came to be dominated by the Pope's influence, Eastern Christianity allowed the bishops and patriarchs of major centres like Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem to express their own unique traditions and identities.

These differences eventually culminated in the Great Schism of 1054 AD, which formally divided the Church into the Roman Catholic Church in the West and the Orthodox Church in the East. This is a pivotal moment in Christian history for GCSE RS students to consider.

Key disagreements included:

Papal Authority: A core disagreement was the issue of papal authority. The Roman Catholic Church, representing the Western tradition, asserted the Pope's claim to universal jurisdiction (authority over all Christians globally) and eventual infallibility (never being wrong when speaking on matters of faith and morals from his official seat, ex cathedra). According to the Roman legate Cardinal Humbert, writing in 1054, "The Roman See... is the head of all the Churches, which God himself made the principal one." The Eastern Orthodox Church staunchly rejected this claim of universal supremacy. While they acknowledged the Pope as being the first among equals (due to Rome's historical significance), they refused to accept his jurisdiction over other patriarchs and bishops. This disagreement over who held ultimate authority in the Church was arguably the primary factor leading to the split.

The Filioque clause (Latin for "and the Son") was another major theological disagreement contributing to the Great Schism. The Western Church added this phrase to the Nicene Creed, stating the Holy Spirit proceeds "from the Father and the Son." The Eastern Orthodox Church strongly rejected this, maintaining the original Creed's stance that the Spirit proceeds "from the Father alone." This wasn't just about a word; it reflected different understandings of the Trinity's internal relations and the authority to change universal creeds. For GCSE RS, understanding the Filioque clause allows you to develop a more nuanced understanding of the Trinity, based upon differing denominational perspectives.

The Great Schism profoundly shaped the distinct identities of Eastern and Western Christianity, creating two separate traditions that persist to this day. Despite this division, Orthodox Christians firmly believe they maintain an unbroken line of apostolic succession, passed down through their bishops from the disciples of Jesus. This, for them, signifies their preservation of the original faith of the early Church, ensuring its theology, liturgy, and practices have remained largely unchanged over the centuries, "standing firm on the rock of faith from generation to generation" (ancient Orthodox saying).

Core Beliefs

Orthodox Christianity shares fundamental beliefs with other Christians (e.g. Jesus as divine and human, the Bible as God's Word) but places unique emphases on:

The Trinity: Like all mainstream Christians, Orthodoxy believes in one God in three co-equal persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. However, they strongly affirm the Spirit's procession from the Father alone as the sole source of divinity, respecting the distinct hypostases (persons) within the Godhead without compromising unity.

Theosis (Deification/Divinisation): This is a central theological concept for Orthodox Christians. It refers to the process by which human beings, through God's grace and union with Christ and the Holy Spirit, can become more like God – participating in the divine nature, but never becoming God themselves. It's a journey of transformation towards holiness and communion with God.

Sacred Tradition: Unlike some Protestant denominations, such as Calvinism, Orthodox Christianity places immense value on Sacred Tradition, seeing it as the living faith of the Church passed down through generations. This includes the teachings of the Church Fathers, the decisions of the Ecumenical Councils, the Liturgy, iconography, and the lives of saints. Sacred Tradition is considered inseparable from Scripture, both together forming the complete revelation of God.

Eucharist (Divine Liturgy): The Eucharist, known as the Divine Liturgy, is the central act of worship. Like Catholics, Orthodox Christians believe in the Real Presence of Christ – that the bread and wine truly become the actual Body and Blood of Christ (transubstantiation), not just symbolically, but mystically and in reality. All seven sacraments are referred to as "Mysteries."

Icons: Icons are highly significant in Orthodox worship and spirituality. They are often seen as the most distinctive feature of their faith. These sacred images of Christ, Mary (the Theotokos), saints, and biblical events are not worshipped themselves but are venerated (deeply respected). They are seen as "windows to heaven," tangible points of contact that help worshippers connect with the divine and understand theological truths. This unique practice is often a focus for GCSE RS questions.

Worship and Practice

Orthodox worship is renowned for its beauty, richness, and sensory experience. Just visit an Orthodox church today! Some key features of worship include:

Divine Liturgy: This is the primary Sunday service, typically longer and more elaborate than many Western services. It is deeply liturgical, involving ancient prayers, chanting, and incense, aiming to transport worshippers into a heavenly experience.

Chanting: Unaccompanied chanting is characteristic of Orthodox services, creating a meditative and prayerful atmosphere.

Fasting: Orthodox Christians observe numerous strict fasting periods throughout the year (e.g., Great Lent before Pascha/Easter, Advent before Christmas), abstaining from certain foods (meat, dairy, sometimes oil and fish) as a spiritual discipline for purification and self-control.

Veneration of Saints and Mary: Saints are deeply revered as examples of holiness and intercessors, particularly the Theotokos (Greek for "God-bearer"), Mary, who is held in the highest esteem as the Mother of God.

Orthodox Saints

For Orthodox Christians, saints are not just historical figures; they are deeply integrated into worship, serving as living examples of faith and as spiritual guides. Their lives demonstrate the journey of theosis (divinisation) – the process of becoming more like God through union with Christ and the Holy Spirit.

Saints are also central to the distinctive Orthodox practice of venerating icons, through which believers connect with the holy person represented. Remembering some of these key figures can add depth and nuance to your GCSE RS essays.

1. The Most Highly Honored: The Theotokos

The Theotokos (Mary, Mother of God): While not strictly a "saint" in the same category as others, Mary holds the absolute highest place of honour in Orthodox veneration, second only to God Himself. She is revered as the "God-bearer" (Theotokos in Greek), uniquely chosen to bring the Incarnate Jesus into the world. Her humility and obedience make her the ultimate example of human cooperation with God's will and a most powerful intercessor for humanity.

2. Apostolic and Early Biblical Figures

St. John the Forerunner (the Baptist): Revered as the pivotal prophet who prepared the way for Christ, baptised him, and identified him as the Lamb of God. He bridges the Old and New Testaments.

The Apostles (e.g., Peter, Paul, Andrew): As the direct disciples of Jesus and the first evangelists, the Apostles are foundational. St. Andrew, for example, is especially venerated as the founder of the Church of Constantinople.

3. Defenders of Orthodox Doctrine (Great Church Fathers)

These 4th-century bishops were instrumental in shaping and defending the core theological doctrines of Orthodox Christianity. The most important ones are known as the Three Holy Hierarchs, or Cappadocian Fathers:

St. Basil the Great: Known for his monastic reforms (earning him the title "Father of Eastern Monasticism"), his contributions to liturgy (the Liturgy of St. Basil the Great), and his theological writings on the Holy Spirit.

St. Gregory the Theologian (of Nazianzus): Celebrated for his eloquent sermons and sophisticated theological defences of the Nicene Creed and the Trinity, often considered the finest orator of the early Church.

St. John Chrysostom ("Golden-mouthed"): Renowned for his powerful preaching and, notably, as the primary author of the Divine Liturgy (the main worship service) celebrated almost daily in Orthodox churches worldwide.

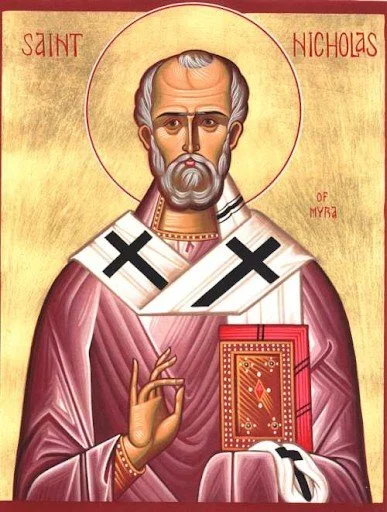

4. Beloved & Popular Saints

St. Nicholas of Myra: Popularly known in the West as the basis for Santa Claus, St. Nicholas was a 4th-century bishop revered throughout the Orthodox world for his exceptional charity, secret generosity to the poor, and numerous miracles, including saving sailors from a storm. He remains one of the most beloved and widely venerated saints.

St. George the Great Martyr: A highly revered military saint, often depicted as a dragon slayer. He symbolises unwavering courage, faith, and martyrdom, having endured immense torture for his Christian faith during Roman persecutions. He is also the patron saint of England, showing that he is venerated outside of the Orthodox world.

Icon of St. Nicholas of Myra, the inspiration behind Santa Claus.

Structure and Authority: Autocephalous Churches

Unlike the Roman Catholic Church's which is centralised under the Pope, Orthodox Christianity is structured as a communion of independent, self-governing churches, known as autocephalous (meaning "self-headed") churches.

Each is led by its own Patriarch or Archbishop.

Authority is exercised through conciliarity, meaning decisions are made collectively by councils of bishops, rather than by a single individual. The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople is considered the "first among equals," holding a role of honour but not universal jurisdiction.

Variations within Orthodoxy

While all Orthodox Churches share the same core theology, liturgy, and sacraments, they often have distinct cultural expressions and historical developments. For GCSE RS, it's useful to be aware of two prominent traditions:

Russian Orthodox Church: This is the largest Orthodox Church in terms of membership. Its history is deeply intertwined with Russian culture and the state. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Moscow came to be seen by many as the "Third Rome," a new spiritual centre of Orthodoxy. It has a rich tradition of iconography and monasticism that has significantly shaped Russian art and literature, including the works of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky.

Greek Orthodox Church: This term generally refers to the various autocephalous churches whose historical roots are in the Greek-speaking world, including the Patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem, as well as the Church of Greece. They are often seen as the custodians of the original Byzantine traditions and liturgy, maintaining a direct link to the historical heartland of Eastern Orthodoxy. Moreover, the New Testament was originally written in Koine Greek, a fact of profound significance for Greek Orthodox Christians. This linguistic link to the foundational texts of Christianity suggests an unbroken line of continuity with the original Word of God.

Nevertheless, despite the prominence of these two traditions, it's important to remember that there are many other autocephalous Orthodox Churches around the world (e.g., Serbian, Romanian, Antiochian, Georgian), all united in core doctrine but reflecting their own national and cultural heritage. While this structure allows for cultural diversity and local adaptation, critics sometimes argue that it can lead to a lack of overall unity in decision-making and global outreach, especially when national churches have political disagreements – such as those surrounding Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Conclusion: Application to your GCSE RS Exam

Understanding Orthodox Christianity is highly valuable for your GCSE RS exams for several reasons:

Demonstrates Diversity: It allows you to illustrate the rich diversity within Christianity, moving beyond just Catholic and Protestant views.

Comparative Analysis: You can effectively compare and contrast its beliefs and practices with other Christian denominations, especially Roman Catholicism (e.g., on papal authority, icons, or the Filioque clause in the Creed).

Specific Practices: Knowledge of unique concepts like Theosis and the veneration of Icons provides specific, in-depth examples of Christian belief and worship, which are excellent for answering "explain" or "evaluate" questions.

Historical Context: Understanding the Great Schism and the distinct historical development of Eastern Christianity adds depth to your answers, showing a comprehensive grasp of the subject.

By considering the unique perspective of Orthodox Christianity, you'll not only broaden your religious knowledge but also gain the ability to provide more detailed, nuanced, and impressive answers in your GCSE RS paper. For example, when tackling a question on the importance of the resurrection, you may refer to the concept of theosois (divinisation) and explain how, for an Orthodox Christian, Jesus' resurrection is the promise that humanity can participate in God's nature and overcome original sin.