Examining the Evidential Problem of Evil (A-Level Philosophy)

In this week’s blog, we're delving into one of the most emotionally charged and intellectually challenging arguments in the Metaphysics of God module: the evidential problem of evil. Unlike the logical problem of evil (articulated by Mackie) which argues for a strict logical contradiction between God's attributes and the existence of any evil, the evidential problem takes a probabilistic approach. It contends that the sheer amount and nature of evil in the world provide strong inductive evidence against the existence of a benevolent and omnipotent God.

Think of it this way: the logical problem aims for a knockout blow, a definitive contradiction. The evidential problem, however, seeks to build a compelling case through the overwhelming weight of evidence. While philosophers such as Rowe accept Plantinga’s ‘solution’ to the logical problem of evil, the evidential problem is often viewed as more difficult to solve.

In what follows, you will learn everything you need to know to ace any related questions in the A-level Philosophy exam.

What is the "Evidence" Against Classical Theism?

The evidential problem focuses on what is often termed gratuitous evil or pointless suffering. This refers to evil that appears to serve no greater good, evils that seem unnecessary for any conceivable divine plan. Consider:

The Holocaust: The systematic extermination of millions of innocent people. What greater good could this possibly serve?

Natural Disasters: Earthquakes, tsunamis, and famines that decimate populations, causing immense suffering to humans and animals alike.

Childhood Cancer: The agonising and premature deaths of innocent children.

Animal Suffering: The vast scale of pain and death experienced by animals in the wild and in factory farms.

The evidential argument doesn't necessarily claim that all evil is pointless. Proponents acknowledge Hick’s point that some suffering might lead to growth, empathy, or the development of virtue. However, they argue that the sheer scale and horrific nature of such evil strongly suggests that a God with the traditional attributes would not allow it.

The Argument Laid Bare:

In standard form, the evidential problem can be rendered thus:

If God exists, then God is omnipotent (all-powerful), omniscient (all-knowing), and perfectly good (all-benevolent).

A perfectly good being would want to prevent all evil that it can.

An omnipotent being would be able to prevent all evil.

An omniscient being would know about all evil.

Therefore, if God exists, there should be no evil that He cannot prevent.

However, there exists a vast amount of evil, including seemingly gratuitous evil, that God could prevent.

Therefore, the existence of such evil provides strong evidence against the existence of God.

Key Thinkers and Perspectives:

William L. Rowe: A prominent proponent of the evidential problem. His "fawn in the forest" example is often cited: a fawn caught in a forest fire, suffering terribly before dying, with no apparent greater good resulting from its suffering. Rowe argues that while it's logically possible a greater good exists, it's highly improbable and we have no good reason to believe it does. This example is mentioned in the A-level Philosophy syllabus.

Paul Draper: Argues for the "hypothesis of indifference," suggesting that the evidence of evil is better explained by a universe that is indifferent to human suffering than by the existence of a perfectly good God. He points to the seemingly random distribution and immense scale of suffering. Draper argues that when we compare the hypothesis ‘an omnipotent benevolent being created the world’ with the hypothesis ‘the universe is indifferent to human suffering’ the latter seems more likely when faced with evidence of widespread arbitrary suffering.

The Problem of Scale: Evidential arguments often emphasise the sheer quantity of suffering throughout history and across the globe. How can this ever-expanding ocean of pain be reconciled with a loving and all-powerful creator who designed the world ex nihilo (out of nothing)?

Responses and Theodicies:

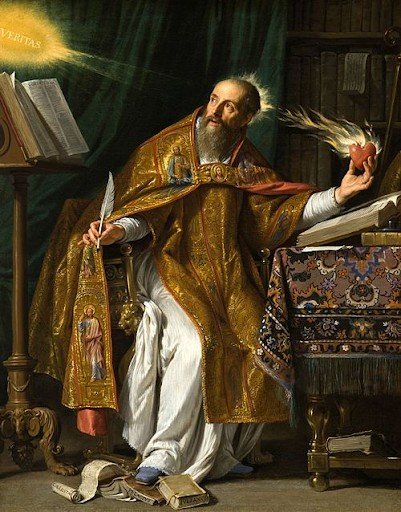

Saint Augustine by Philippe de Champaigne

Theists have offered various responses to the evidential problem, attempting to reconcile God's attributes with the evidence of evil and suffering in the world. These are often referred to as theodicies:

The Free Will Defence: Argues that God allows evil because it is a necessary consequence of granting humans free will, which is itself a great good. This response was offered by Saint Augustine who argued that it is logically impossible for God to grant humans the higher good of free will without allowing for the possibility of evil. However, evidential problem proponents often question whether all evil, particularly natural evil and the suffering of innocents, can be attributed to God giving us free will.

The Soul-Making Theodicy: Suggests that God allows evil as a means for human beings to develop virtues like compassion and resilience. Suffering is a necessary part of this "soul-making" process. This response was formulated by the Greek Bishop Irenaeus (born 130 AD) and is often called the ‘Irenaean theodicy’. However, it was developed in modern times by the philosopher, John Hick, and it’s his version that primarily features on the A-level Philosophy syllabus. For Hick, God allows for certain first order evils, like pain and illness, so that humans can cultivate second order virtues like courage. Critics argue, however, that the sheer scale and intensity of some suffering seem disproportionate to any potential soul-making benefits. It is difficult to argue, for example, that child sexual exploitation contributes to soul-making, or that the holocaust was a fair price to pay for moral improvement.

The Mystery Theodicy: Claims that God's ways are beyond human comprehension, and we cannot possibly understand the ultimate reasons for allowing evil. While acknowledging human limitations, critics argue that this response can feel like an abdication of reason and doesn't adequately address the apparent pointlessness of some suffering- it simply obscures the problem by claiming we can’t find an answer.

Skeptical Theism: A more recent response that argues we are in no position to know whether a seemingly gratuitous evil truly is pointless. Our limited cognitive abilities prevent us from grasping the full scope of God's plan. Critics argue that this can lead to accepting any amount of suffering without question. It also places strong epistemic restrictions on the extent to which we can understand God and his attributes.

In Conclusion:

The evidential problem of evil presents a significant challenge to theistic belief. By focusing on the apparent pointlessness and overwhelming scale of suffering, it argues that the existence of such evil provides strong inductive evidence against the existence of a benevolent and omnipotent God. While various theodicies attempt to reconcile these seemingly contradictory realities, the debate remains a crucial area of philosophical inquiry.

For A-Level philosophy, your task is not necessarily to "solve" this problem, but to understand the nuances of the arguments, critically evaluate the different perspectives, and develop your own reasoned position in response to the question. What do you find the most compelling aspect of the evidential problem? What responses, if any, do you find convincing? Do any of the theodicies, such as Hick’s ‘soul-making’ argument, raise the probability of God’s existence in the face of seemingly pointless suffering?

Success in the A-level Philosophy exam hinges on crafting clear, logical arguments that directly address the question. Eliminate redundancy and maintain focus. Structure your response strategically, addressing weaker objections initially and progressing to stronger ones. Demonstrate the 'principle of charity' by presenting opposing viewpoints fairly and judiciously. This approach strengthens your own arguments and showcases your analytical depth.